13 NOVEMBER 2022

Energy

Technology enables, productivity as stored energy and hustle should also be about displacement

“Use less” is the accepted mantra when it comes to the basic utilities of day-to-day living — electricity, water, gas, fuel and so on.

On the surface level, it appears to be a ‘common sense’ rule of thumb. Be conservative, use less than necessary, do not overextend — why not, right? These concepts make sense when I consider elements that are external to my being, but they exist in complete contradiction to the mode of operation for my mind and body.

Here is what I mean.

When I wake up in the morning, often there is this pressure that is at the front of mind, a subtle force that is exerted by the awareness that the hours of the day have already began counting down from the very moment my eyes are open. There is something that feels wasteful of burning up a day’s worth of allocated energy by not putting it to good use, and as obvious it might be, it serves as a useful reminder of the fact that time is a finite resource.

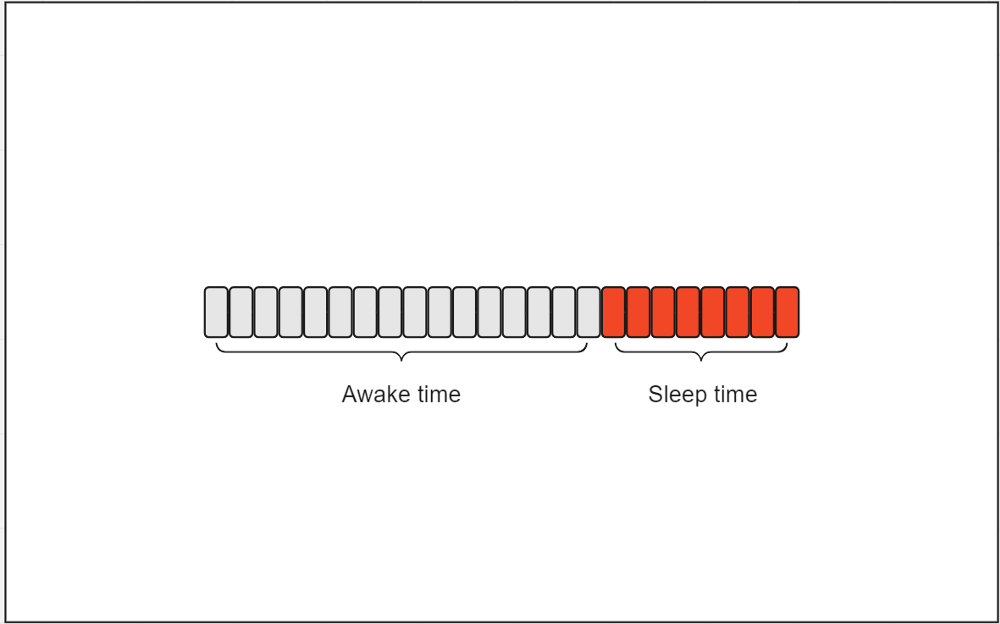

Here, I draw a line that connects time and energy because they instinctively seem to be tightly interlinked. The amount of potentially useful time I have access to in a day is dependent on the amount of energy that I am able to tap into and vice versa. As a biological being, roughly a third of all my days are by default allocated to sleep — a hard constraint that is part and parcel of being human. After this deduction, the remainder is a 16 hour window of time and energy.

“OK, so what do I really want?”

“To maximise my time and to maximise my energy, because all other desires are downstream of these two primary bottlenecks.”

“OK, how might I achieve this?”

The how question requires more of an explanation, which we will now get into.

"What comes to mind when you think about the word 'technology'"?

For me, the obvious ones would be the iPhone, Google Maps and economy air travel — but, as it turns out, these only form a minority subset of the vast ecosystem of technology that permeates through the various aspects of modern living. 'Technology' also includes the 'boring' things like the Toyota Camry, the kettle that you use to speed boil water in the morning, the on-demand supply of electricity that gives you the ability to light up the interior spaces that you live within and much, much more.

The next question: "why is technology important?"

Mankind invented technologies as the means for enabling ourselves to do more with constrained resources, beyond what was previously conceived as possible.

The washing machine allowed people to outsource the cleaning of their clothes away from their hands and to the press of a few buttons.

The combustion engine allowed people to travel far beyond, more comfortably and quicker than what came before — the horse and carriage.

If we rewind the clock even further, as Yuval Noah Harari articulated in ‘Sapiens’, the invention of fire and the cooking of food were the technologies that allowed the human species to prioritise the development of the brain and our cognitive capacities over internal digestive processes — these technologies allowed us to outsource the task of extracting maximum nutrition from the things we eat away from our stomachs to the availability of higher quality, more nutritious food.

The next question: "what is the purpose of technology?"

Perhaps a way to answer this question is to fall back onto the previous answer and to focus on the function of technology — which is to save ourselves time and energy that would have been by-default consumed through intensive, laborious, repetitive, but necessary, tasks. But I think this question leans more towards the mystery of why, and one answer could be as follows: the purpose of technology is to free up more of those precious and finite human resources of time and energy so that they could be spent on work that is even more productive than what existed previously.

With this lens, technology is an enabler not because it allow us to ‘use less’ — in other words, to do the things we currently already do but with less energy and time — but because they unlock the option of doing far more than what humans previously conceived as possible.

The next question: "what is productive and what is not productive?"

While not all-encompassing, I will borrow some words from Adam Smith to create a skeleton framework for trying to attempt an answer to this.

“A man grows rich by employing a multitude of manufacturers; he grows poor by maintaining a multitude of menial servants. The labour of the latter, however, has its value, and deserves its rewards as well as that of the former. But the labour of the manufacturer fixes and realises itself in some particular subject or vendible commodity, which lasts for some time at least, after that labour is past. It is as it were, a certain quantity of labour stocked and stored up, to be employed, if necessary, upon some other occasion…

the labour of the menial servant, on the contrary, does not fix or realise itself in any particular subject or vendible commodity. His services generally perish in the very instant of their performance, and seldom leave any trace of value behind them, for which an equal quantity of service can afterwards be procured.”

I like this frame because it is easy to criticise oneself for engaging in seemingly menial actions such as leisurely reading, watching Netflix or socialising with friends and feeling an ambiguous sense of guilt for being ‘unproductive’, when they can actually be highly useful for our overall wellbeing.

Instead, a productive action is distinguished from an unproductive action by its capacity to generate outcomes that are capable of persisting beyond the present moment and which can be called to serve some value in the future when deemed necessary.

Some tasks that come to mind that fit into the ‘unproductive’ category would include common chores like doing laundry, washing dishes, sleeping and cooking food — all important events but not necessarily very good at persisting over time.

One of the initial assumptions that was made in the beginning was about time and energy and how they are both tightly interlinked.

A clean visual representation of this is through a high school physics analogy:

In the formal definition of ‘power’, energy and time are quantified to be inversely proportional.

Then we can expand this further, as energy expended is equivalent to ‘work’ produced:

Then, what is work? Work produced is equivalent to force applied by a specific displacement over time.

Finally, cancelling out time leads to the final result:

This final form is neat because it tells us that given an allocated amount of energy, we can then determine how much force to apply by what displacement.

Why is this useful? It allows us to reframe the earlier two diagrams in the following way.

This is the revised proposition: the total amount of available energy and time in any one day is, by default, categorised as unproductive out of the gate — regardless of whether we choose to take action or not, the consumption of energy is inevitable.

This then leads to a new hypothesis: it is through conscious effort and the application of force that we can convert this unproductive allocation of energy into resources that can be more productive.

Displacement is the second parameter that is of high importance, because maximal application of force at minimal displacement is not a very effective use of that energy — in machine terms, this could be considered as the wasteful generation of heat.

The engine of a car that is revving at 8,000 rpm but not turning the wheels of the vehicle is not very useful — generated from plenty of force but leading to no displacement.

Displacement is highly dependent on the method of application of force, but if successful, the outcome might look like this:

To the singular end of productivity, it is obvious that energy is best utilised through applications where force required is lowest but displacement is maximised.

Higher fidelity definitions of these four quadrants are as follows:

- High force, high displacement — intense effort but worthwhile in pursuit of a short term objective

- High force, low displacement — not ideal, but sometimes necessary to push through

- Low force, high displacement — humming and in the zone

- Low force, low displacement — spinning the wheels, going nowhere

To close, a note on hustle culture.

In our society today, there is a strong sense of pride in upholding the identity of a ‘hustler’ — someone who is willing to put his nose to the grind stone, to show up and to do the reps when most others are still sleeping, to push through and to take on that overtime. This is a powerful force, but it seems like there might not be enough conversation around displacement.

Yes, work hard and run like a maniac when the time comes and you are called, but also step back every once in awhile and ask yourself this:

“Am I expending my force optimally and getting to where I need to go? Or am I just spinning really fast but going nowhere?”

Perhaps, one’s hustle determines the force that one can exert, but it is also important to cultivate a tacit knowledge of where the application of force might be most useful.

“People think focus means saying yes to the thing you’ve got to focus on. But that’s not what it means at all. It means saying no to the hundred other good ideas there are. You have to pick carefully. I’m actually as proud of the things we haven’t done as the things I have done. Innovation is saying no to 1,000 things.” - Steve Jobs